Vietnam is at a crossroads as it pursues the ambition of becoming the world’s factory, drawing increasing global attention and foreign direct investment (FDI). Recent disruptions, such as the US–China trade war and the COVID-19 pandemic, have reshaped global manufacturing, positioning Vietnam as a pivotal destination for FDI through both friendshoring and nearshoring strategies. However, while Vietnam’s path toward global manufacturing leadership is promising, it is also marked by potential challenges.

Over the past two decades, Vietnam’s economy has grown rapidly, with GDP expanding by more than 6% per year — the fastest rate in ASEAN. This impressive growth is driven by an export-oriented model. Exports have surged from just 4% of GDP in 1988 to over 94% in 2022, making Vietnam second only to Singapore in the region. The dramatic rise in export share highlights Vietnam’s resilience and ability to rebound even after global shocks.

Vietnam’s integration into global supply chains began with the Doi Moi reforms in 1986, which opened the country to foreign investment. Once reliant on agricultural product exports, Vietnam has since shifted its economy toward manufacturing, attracting substantial FDI into its industrial sectors. Since the Doi Moi reforms, Vietnam has experienced three distinct waves of FDI, with annual inflows rising from nearly zero to approximately USD 18 billion, consistently accounting for 4–6% of GDP. FDI is geographically concentrated, with 42.7% of total investment in the Southern Key Economic Zone (SKEZ) and 29.4% in the Northern Key Economic Zone (NKEZ). East Asia is the dominant source of FDI, led by Korea (18%), Singapore (16%), and Japan (16%) of accumulated registered capital from 1998 to 2023. The most recent wave of FDI, beginning after 2016, coincides with the US–China trade war and the rise of friendshoring, prompting multinational corporations—especially in electronics, such as Samsung and Intel—to relocate or expand production in Vietnam. According to Figure 1, over the past two decades, manufacturing has now dominated both the number of FDI projects and the total value of capital, accounting for 60% of total investment.

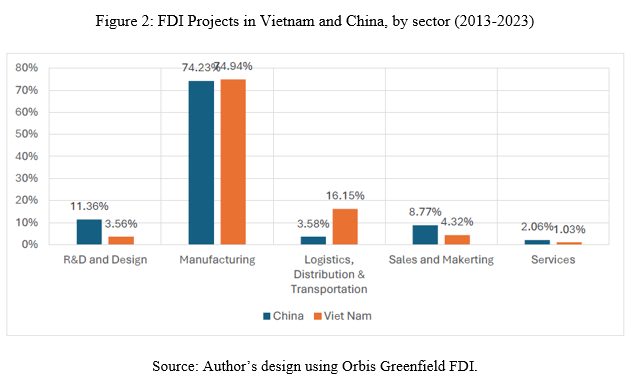

Despite this surge in manufacturing, much of the capital is concentrated in low-value-added assembly and is heavily dependent on imported components, particularly from China. The “smiling curve” theory highlighted in the report illustrates that the highest value in global supply chains accrues at the stages of design, research and development, and branding—areas where Vietnam remains weak. Most FDI projects are focused on assembly and logistics, leaving Vietnam at the lower end of the value chain. Figure 2 clearly contrasts Vietnam’s FDI structure with that of China: Vietnam receives more investment in logistics, while China attracts far more investment in high-value stages such as R&D and design. This is further reflected in Vietnam’s low domestic value-added share in exports across four key industries—electrical equipment, machinery, textiles, and furniture—all of which have value-added rates below 50%, and are significantly lagging behind those of China, ASEAN, and OECD countries.

Vietnam’s attractiveness to investors is anchored in several competitive advantages. The country boasts a young and concentrated workforce of nearly 100 million, providing both scale and cost benefits. Labor force participation and output growth per worker are among the highest in the region, and average wages remain lower than in China, making Vietnam appealing to cost-sensitive manufacturers. Its geographic proximity to China and strategic location in Southeast Asia make it a natural choice for supply chain diversification under the “China Plus One” strategy. Furthermore, the government has fostered a favorable investment climate with low corporate tax rates, generous land rent incentives, and a wide network of free trade agreements, all of which have reduced barriers and enhanced investor confidence.

Nevertheless, Vietnam faces considerable structural headwinds. The demographic dividend is eroding rapidly, with projections indicating that by 2050, over 20% of the population will be over 65, shrinking the labor pool and raising dependency ratios. While Vietnam has a large workforce, productivity and the share of high-skilled workers remain below regional competitors. Only 5.3% of manufacturing workers are classified as high-skilled, and investment in R&D is minimal. This limits Vietnam’s ability to move up the value chain. Governance and bureaucracy also pose persistent challenges in terms of administrative complexity, regulatory hurdles, and corruption. Although anti-corruption campaigns have improved Vietnam’s global rankings, they have also led to bureaucratic delays, deterring some investors and slowing FDI approvals.

Vietnam’s ascent as a manufacturing powerhouse is clear, but its future as the world’s factory depends on overcoming the low-value-added trap. To achieve this, Vietnam must invest in workforce upskilling and education to enhance productivity and innovation. The country needs to attract FDI in high-tech, R&D-intensive sectors rather than relying solely on assembly lines. Streamlining bureaucracy and improving governance are essential for building a more transparent and efficient business environment. Additionally, Vietnam must diversify its supply chains and reduce over-reliance on China, especially in critical industries.

In conclusion, Vietnam’s economic progress over the past few decades has been driven by three significant waves of FDI, transitioning from a focus on natural resources to manufacturing. However, moving to the next stage will require a decisive shift toward higher value-added, technology-intensive industries, supported by strategic investments in infrastructure and human capital. Most importantly, effective and transparent governance will be crucial to enable these transformations and secure Vietnam’s position as a leading global manufacturing hub in the future.

By LU, Miranda

Researchers: BANH, Thi Hang, HUA, Thanh Phong