In the wake of global de-risking policies, the narrative has largely focused on how ASEAN benefitted from FDI relocation, but very few discuss that the region stands to lose considerably as well. A recent study by researchers at ACI examines this less-studied strand of research to find that ASEAN faces indirect spillovers and collateral damage risks from the global de-risking trend away from China. ASEAN intermediate products are the most susceptible to such de-risking, with the risks amplified in the textiles, chemicals, electronics, and metal sectors.

ASEAN’s export concentration to China significantly contributes to its negative spillovers as the G7 de-risks from China. While aggregate data on risk concentration shows that ASEAN’s export share to China is around 18%, it underestimates the true scale of exposure – assessing the varying levels of risk concentration across individual products for each ASEAN member reveals that over 20,000 products have an export concentration to China up to 20%. This percentage exceeds 70% for some 2000-odd products. If the global demand for Chinese products dwindles, multiple ASEAN suppliers will feel the pinch.

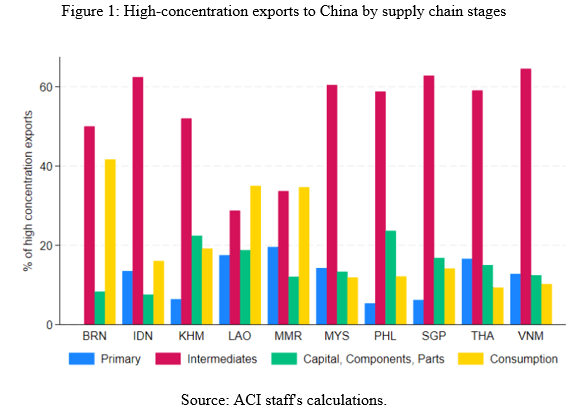

Regarding supply chain stages, ASEAN exports to China are majorly clustered in intermediate goods and raw materials. As illustrated in Figure 1, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam account for more than 60% of such exports.

But which sectors’ intermediate inputs face the greatest risks of harmful indirect spillovers and potential collateral damage? The answer lies in identifying the major high-concentration Chinese imports targeted by the G7 to de-risk from and then employing input-output tables to examine which ASEAN products constitute a major chunk of Chinese imports. This exercise shows that textiles, chemicals, metals, and electronics may be subject to the G7’s de-risking moves, and nearly 20% of ASEAN’s exports to China consist of these sector-specific inputs. Should these supply chains be disrupted, ASEAN input suppliers may encounter damaging economic consequences in the short run.

Such vulnerabilities signal the need for ASEAN governments to devise strategies that allay the negative impacts on businesses susceptible to indirect spillovers and collateral damage due to de-risking. These can include financial support like tax breaks and grants to encourage investments in alternative supply chains to diversify risks.

In this intertwined global trade landscape, the ASEAN nations must demonstrate prudence and strategic decision-making. As countries move to target Chinese products in their de-risking journey, the ASEAN governments must ensure that the large volume of input suppliers to China are shielded from unfavourable economic repercussions. There is a need to promote the diversification of economic and trade relationships such that ASEAN can cushion the impact of such indirect spillovers.

Researchers: YI, Xin