Summary:

Critical minerals have become a focal point in geopolitical discourse, driving discussions on collaboration and contention. Their importance lies in their irreplaceability in key manufacturing sectors and the volatility of their supply chains due to the geographic concentration of reserves and production. Against this backdrop, what does India’s critical minerals supply and demand landscape look like?

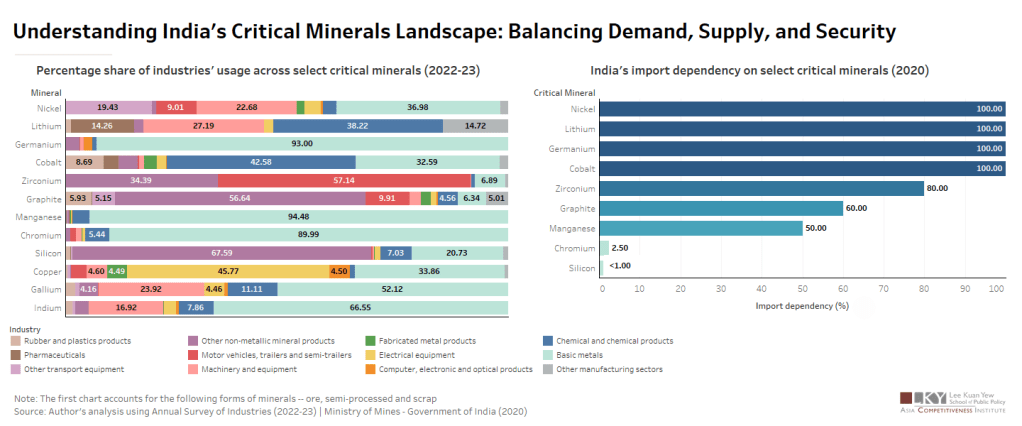

In 2023, the Government of India identified 30 critical minerals based on the country’s needs. Figure 1 maps the use case of a subset of these critical minerals across industries, using manufacturing input data from the latest Annual Survey of Industries. The consumption of Nickel, Lithium, and Cobalt are distributed uniformly across multiple industries. Basic Metals is the dominant sector for the consumption of Germanium, Manganese, and Chromium. Zirconium is heavily used in Motor Vehicles, trailers, and semi-trailers sector, followed by the Other non-metallic mineral products sector, which also dominates Graphite and Silicon consumption. Electrical equipment manufacturing heavily relies on Copper. Gallium and Indium are used in significant portions in Machinery and equipment production.

India’s demand for critical minerals is expected to rise exponentially, and this industrial consumption mix will be ever-evolving, driven by its clean energy goals and initiatives to localize the manufacturing of heavy high-tech industries like Solar PVs, Wind Energy, Electric Vehicles, and advanced energy storage solutions.

While nickel, graphite, and copper currently have a single-digit share of the motor vehicle industry’s consumption, this is expected to change. According to the Economic Survey of India 2023, India’s EV market is projected to grow at a 49% CAGR between 2022 and 2030, with a national target of 30% EV penetration by 2030. To support heavy manufacturing, the Indian Union Cabinet launched the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme—a financial incentive program aimed at promoting domestic production—for Advanced Automotive Technology (AAT) products and Advanced Chemistry Cell (ACC). The schemes have a budgetary outlay of USD 3.46 billion and USD 2.41 billion, respectively, to drive the production of electric and hydrogen fuel vehicles, as well as giga-scale battery manufacturing. By 2023/24, combined investments of USD 635.4 million had been actualized under these initiatives. As India ramps up EV production, critical minerals like lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese, graphite, and copper will experience increased demand from this industry.

Solar photovoltaic cells and solar batteries require a plethora of critical minerals, most predominantly silicon, copper, and aluminum. India aims to achieve 450 Gigawatt (GW) of installed renewable energy capacity by 2030, with solar accounting for over 60% (approximately 280 GW). With a current installed capacity renewable energy capacity of 125.15 GW in FY23, the industry is ripe for growth. PLI outlay for Renewable Energy was USD 3.2 billion and out of the potential outlay, USD 960.4 million worth of investments were actualized by FY 2023/24 for High Efficiency Solar PV Modules for setting up of approximately 48,337 Megawatt capacity of fully integrated Solar PV Module manufacturing units, thus increasing the demand for critical minerals from the associated sectors.

Semiconductors, a mineral-intensive component of most modern electronic devices, also require many critical minerals for production, including but not limited to Gallium and Germanium. India is pushing to become a key player in the global semiconductor supply chain, enabled by the India Semiconductor Mission (ISM). The ISM, launched in 2021 with a USD 10 billion outlay subsidizing 50% to 70% of initial capital investments for new manufacturing units, aims to build a fully integrated semiconductor ecosystem domestically, from design to fabrication to assembly. As India advances its semiconductor initiatives—such as the launch of ISM 2.0—chip manufacturing is set to expand. A fabrication unit has already been approved in Gujarat, with four additional assembly plants underway. Consequently, the demand for critical minerals will continue to rise.

On the supply side, India is heavily import-dependent, relying entirely on imports for nickel, lithium, germanium, and cobalt. Its import dependency stands at 80% for zirconium, 60% for graphite, and 50% for manganese, while dependence is negligible for chromium and silicon. Notably, these imports are concentrated among a few supplier countries, further amplifying supply chain vulnerabilities. China, for instance, is a dominant supplier for nickel, lithium, cobalt, and graphite, highlighting India’s overreliance on a single country. Japan, Belgium, Australia and Africa also play a crucial role.

Recognizing these vulnerabilities, India has adopted a two-pronged strategy to secure its critical mineral supply chains: forging strategic partnerships with resource-rich countries and increasing domestic exploration and processing. In 2024, India launched the National Critical Minerals Mission for this purpose.

In 2022, India signed an MoU with Australia to facilitate Indian investments in Australian critical mineral projects. In 2024, it strengthened ties with the U.S., aiming to eventually convert this partnership into a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) focused on critical minerals. Since 2024, India has also been actively acquiring critical mineral assets in Africa to diversify its supply sources. Looking ahead to 2025, potential partnerships include investments with Saudi Arabia and technology transfer agreements with Israel, further bolstering India’s mineral supply security.

On the domestic front, it has increased exploration of these minerals through the Geological Survey of India, with exploration projects doubling between 2020-21 and 2023-24. These efforts are showing results, with new discoveries of critical minerals and mine auctions taking place. India also eliminated customs duties on the majority of critical minerals in the Union Budget 2024-25. However, challenges persist, such as low response to auctions due to a lack of technical know-how. There is a long way to go, but India is making steady progress.

Highlights:

1. Currently, critical mineral consumption in India is concentrated in low-tech downstream industries like basic metals and chemicals. However, as it expands its high-tech heavy industries such as EVs, renewable energy, and semiconductors, demand for these minerals will rise significantly.

2. India remains heavily reliant on imports for key critical minerals, including lithium, nickel, cobalt, and germanium, with supply chains concentrated in a few countries, amplifying vulnerabilities.

3. India is actively securing its critical mineral supply through domestic exploration, mining, and refining efforts, alongside strategic international partnerships.

Article By GUPTA, Riddhimaa

Graphic By BALAJI, Akshaya