The rapid advancement of technology has transformed the global competitive landscape. Nations develop expertise in novel technologies while older ones are becoming obsolete. Cutting-edge innovations like 5G, AI, and quantum computing have become focal points for both developed and emerging economies. A study by ACI investigates how strong “path-dependent” is the innovation and technology transition process.

Using the 1992-2019 patent data from PATSTAT sourced from the European Patent Office, the study constructs the “Innovation Space” to analyse the technological linkages and the pattern of innovation across the world. The findings underscore the strength of “path dependence” in predicting technology transition. New technologies are often built on existing frontier knowledge, known as the “standing-on-shoulder” effect.

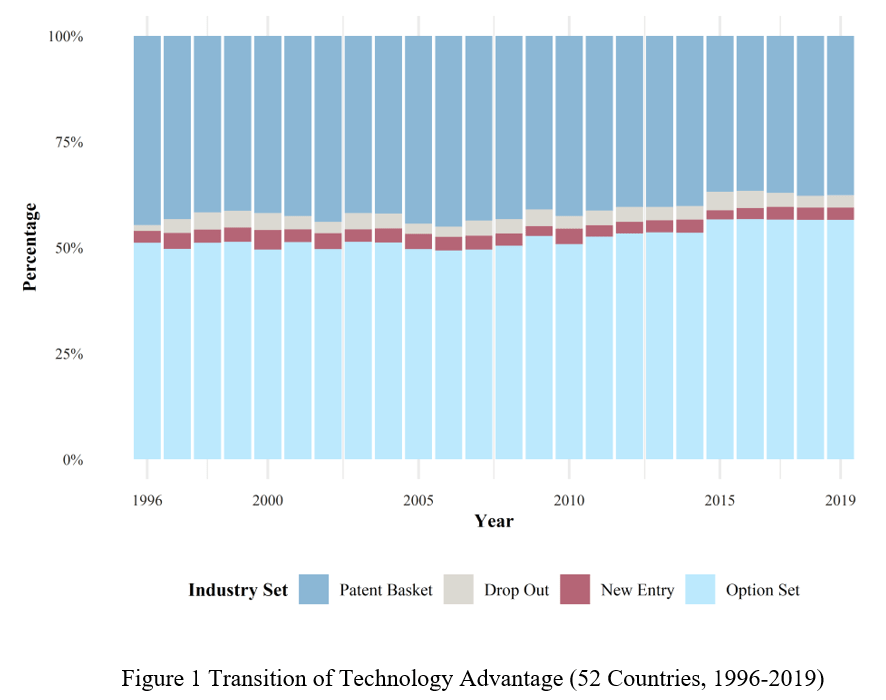

A country’s existing frontier knowledge is quantified by its Revealed Technological Advantage (RTA) Index. This is calculated by comparing its patent share in a specific technology with the world average. If a country’s share exceeds the global average, it possesses technological advantages; otherwise, it does not. The findings unveil stability in RTA across countries between 1992 and 2019. On average, more than 90% of the technological advantages or disadvantages persisted from one year to another. Every year, only 6% of the countries’ disadvantages evolved into advantages (Figure 1). These 6% technologies are called “new entries”.

Further analysis of technological linkages demonstrates that the new entries are not randomly selected but significantly linked to previously advantageous areas. Countries build up advantages based on their knowledge or know-how in other similar fields. This is because resource sharing and transformation make it easier to launch innovation in “related” industries. For example, a country specialising in wood production is more likely to enter the furniture industry than the leather industry. Having established RTA in furniture, the country will find it easier to develop RTA in electronics, compared to when it only specialised in wood.

Upon closer examination of country-level data, the US’s RTAs stayed stable from 2002 to 2019, indicating that its technologies are mature. The US maintains its advantage in the high-tech industries, computer programming, computer & electronics, and pharmaceuticals. In contrast, China’s RTA changes are drastic. As presented in Figure 2, it moved away from low-value-added industries or resource-intensive manufacturing industries, such as refined petroleum and wood. Of all the industries, the most notable advantage-gaining sector is computer programming. Without a solid foundation in the computer electronic manufacturing industry like the US, China has carved a hard way out in its IT sector. Despite significant progress, China’s RTA in computer programming only marginally exceeded the global average by 2019.

The study offers policy implications for developing countries. While developing countries may initially face limited innovation capabilities and find themselves at the lower rungs of the innovation ladder, the observed path-dependency suggests a cost-effective shortcut. By directing innovation resources to high-value-added sectors within the same existing technological cluster, developing nations can chart a successful course through the intricacies of the innovation space.

By HUANG, Yijia

Researchers: YAN, Bowen, ZHANG, Chi